My favorite way to market a fiction collection is also the

most common: displays. Saricks agrees that it’s “one of the most effective ways

to promote and market parts of our collections” (139). It’s easy to lose

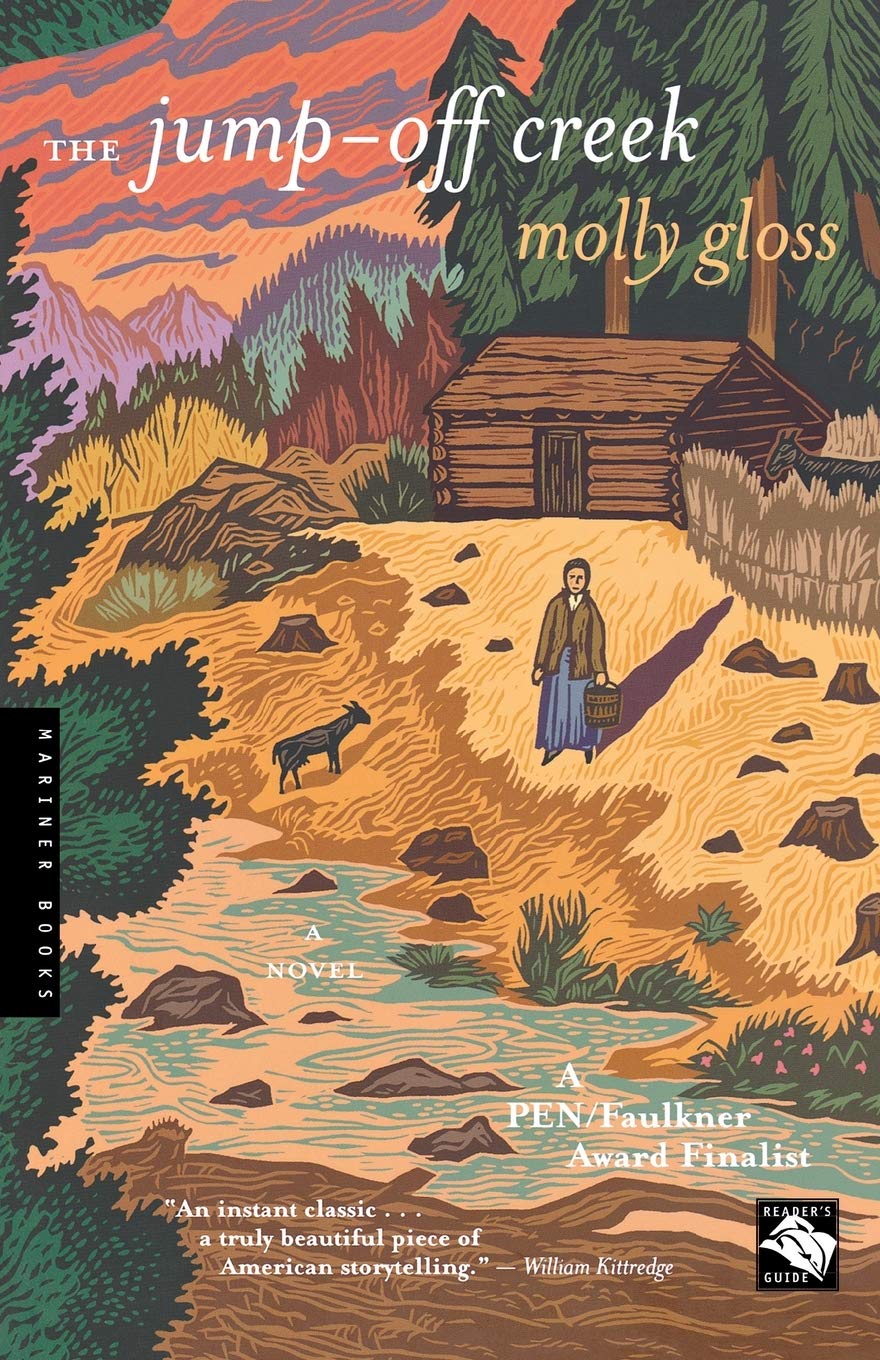

individual titles when you can only see the spines, so any excuse to get those

books face out helps patrons differentiate and find something of interest. It’s

bad to judge books by their cover, but if it works it works.

My library (along with probably every other library) is a

big fan of displays, even when we don’t always have the room. So far, the

branch where I work has mostly created thematic displays, which are extremely

useful for patrons with certain interests. Displays on Amish romances, new

mysteries, holiday cozies, book-to-movie adaptations, etc. are a great way to

feature the collection’s variety and get patrons interested in what else the

library has to offer. My favorite type of display (which I hope to use more in

the future), though, are the more novelty displays. Blind Date with a Book, Anti

Staff Picks (books the staff hated), Saricks’s idea of Good Books You May Have

Missed (or, similarly, Recently Returned), and pretty much anything else that

can immediately grab the patron’s attention are fantastic marketing

opportunities.

The librarians at my work are also really good at integrating

the fiction collection into their programming. There are often displays of

similar titles next to signs for upcoming events (i.e. novels about

quilting/craft clubs by fliers for quilting programs). The librarian who conducted

the book club discussion (from earlier this semester) also makes a table of

readalikes for each meeting’s book club title. The children’s librarians also

do this with their storytimes, so this could really apply to any aspect of the

collection. Combining relevant fiction titles to each program (whenever

possible) can be a good way to market the collection and the program simultaneously.

A few prompts ago, someone on here (please tell me if it’s

you!) suggested making a choose your own adventure for navigating horror

titles, and this would also be an excellent idea for fiction in general. I

would really like to formulate a big sign with a sort of J-14 style quiz* where

a patron can choose between book length, tone, etc. (happy or sad, scary or

heartwarming, funny or serious, etc.) and have each of the “results” boxes at

the bottom have slips of paper with titles to choose from. This way, the patron

could try something new, but there’s a lesser chance of another patron getting

the same result (and the book not being available). It doesn’t necessarily even

have to be this specific model, but any kind of interactive activity could help

engage the patron with the collection. This would also really help with passive

reader’s advisory, mixing the benefits of form-based and list-based RA (both of

which were suggested by the State Library of Iowa in “Don’t Talk to Me”).

Finally (and this idea could end up being cheesy), my

library’s been having big names in the community (newscasters, the mayor, etc.)

do virtual storytimes during the pandemic and sharing it on their social media.

A similar practice where local celebrities share their favorite/current reads

from the library could also be a huge boost for the collection. They could make

a video talking about their favorite book(s) for the library’s social media or

just send a list for displays. “Don’t Talk to Me” also suggested use of shelf

talkers in passive RA, which might be perfect for this. Regardless of format,

their endorsement would be a really good way to market both the fiction

collection and the library overall.

*J-14 Style quiz format (although the library version would obviously have different graphic design choices and no giant pictures of Tom Felton):